Beginning of the end for direct distribution?

The backbone of CPG distribution seems to be a shaky wicket. eB2B operators are using the B2C e-commerce playbook to own retailers. Will this relationship replace direct distribution?

After a long hiatus, back with a new piece on direct distribution. Not really about insurgent brands, but a change in the distribution dynamics means it will impact the CPG industry at large. There is a lot of churn in the distributor community as well. So, I felt this piece is timely. Hope you enjoy reading it.

For decades, the traditional CPGs grew on their direct distribution model. In post-independence India, businesses had no choice but to build their own distribution networks. Over time, as the market matured, direct distribution became a massive moat for traditional brands. As brands grew, their distribution networks became complex, with more intermediaries added to serve far-flung markets. The distributors are individual business owners or family businesses - not run by any professional management. Despite the complexity and multiple hand-offs, the system worked. Still works. This direct distribution still serves the ubiquitous kirana stores - salesmen take orders at set intervals, and products are delivered to stores via distributors or stockists.

Deep, owned distribution is such a big moat that few new brands made it national, even in the early 2000s. The arrival of e-commerce changed the dynamics. We now have brands that start in the digital channel, move to physical retail and make their way to international markets. Physical retail has forced some insurgent brands to build their own distribution. The traditional brands, too, are growing on this new digital channel - e-commerce now accounts for 6-8% of retail CPG sales. The modern trade formats (DMart, Reliance Retail etc.) account for another 11-13% of the CPG sales. So the Kirana stores, general trade, still account for 80% of CPG sales. So, the direct distribution channel gives the traditional brands control of the market.

Own the kirana relationship

But now, this direct distribution moat is under severe attack from B2B e-commerce players. By adopting the e-commerce playbook, the eB2B operators do everything to own the kirana store relationship. In the direct model, brands owned the distributor relationship, not the retailer. The difference might seem small, but it can have huge implications on kirana behaviour.

With so many options, the retailer can buy from anywhere. Taking a leaf from the e-commerce model, the eB2B operators offer better prices and a more comprehensive selection (multiple brands). So, it is natural to expect the kirana stores to gravitate towards this channel. The eB2B operators offer liberal credit terms, financing, and assured delivery to further lock in the retailer. With an integrated model (wide selection, credit, tools and logistics), the eB2B operators present a formidable challenge to direct distribution channels.

Pure-play B2B is not differentiated enough.

Before eB2B, we had large pure-play B2B players such as Metro Cash & Carry. Metro has been operating in India since 2003 but has failed to build a profitable business. Metro has put its India assets on sale. The list of suitors for Metro is quite diverse, including Swiggy. We can write an entirely separate piece dissecting Metro and the pure-play B2B. Still, it suffices to say that the pure-play model failed because it was slightly better than the direct distribution model, with no incentives other than price.

The pure-play operators offer a comprehensive selection of brands and products but no built-in credit or doorstep delivery. The kirana stores had to make monthly or fortnightly trips to the large store, make purchases and ship on their own. With eB2B, it was a no brainer for the retailers to shift.

Metro's belated attempts at offering finance (through NBFC, bank partnerships), providing retailers technical tools, delivery tie-up etc., came in too late. Metro could have done better had it focussed on building services and lock-in retailers sooner. Metro pulling signals the beginning of the end for direct distribution.

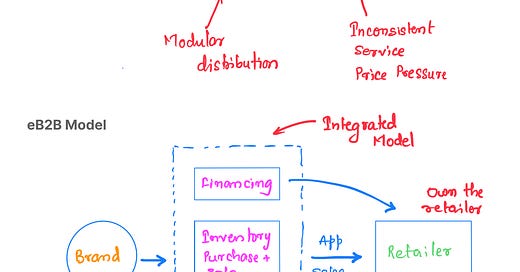

Integrated vs Modular Distribution

The direct distribution model comprises modular components - distributor, distributor/third-party logistics provider, and channel financing provider. These modular pieces are different for different states, cities, towns etc. So the last-mile experience is inconsistent, and retailers don't like it. For a long time, brands have leaned on their distributors to deliver products and services. The distributors must purchase inventory and push it to the retailers using the brand's incentives and subsidies. In a highly competitive market, the retail uptake is low, and costs are increasing, so the distributors have to cut corners, resulting in a poorer retailer experience.

Even when channel financing is available, there are barely any takers. Who wants another lengthy KYC and credit evaluation process? In contrast, in eB2B, the data sharing and credit evaluation are more integrated and seamless. Also, eB2B players tend to set up their own NBFC and carry loans on their own books - taking a more risky position in the value chain.

The eB2B operators believe that an integrated service provider from brand to kirana is a better model. All the three elements, the inventory, financing and logistics, are bundled into one service and provided to the retailer at their doorstep. The integrated approach also allows eB2B players to create multiple profit pools - private label, lending and so on. Say profits from the lending business can provide much-required cash comfort for the inventory business. In the direct distribution model, the distributors are too small to pull off something like this - an average distributor balance sheet might at best be a few ten crores.

Distribution is a high volume, low-value business, so the margins are wafer-thin. So an integrated approach allows eB2B operators to squeeze out every possible percentage point from the various services. Most big eB2B operators are well-capitalized, and with their operations closing in on operational profitability, we can expect eB2B to be around for a while.

The Chaos

The result is chaos for the traditional brands. The brands can neither let go of their distribution control nor can they deny supplies to eB2B for long - the brands are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

From the distributor's perspective, the solution is simple - match the price. The brands can't do this ever. One, eB2B is discounting the products on their books; why should brands take this hit? Two, the traditional brands are constantly under pressure to deliver better margins; these ratios are tied to their stock prices. Moreover, no way brands will reduce their prices in an inflationary market.

The balancing act of working with multiple conflicting channels - denying supplies, resuming supplies, handling protests from distributors and the cycle repeats - is not sustainable in the long term.

Taking cues from closing pure-play B2B operators, the traditional brands have to rethink their options. We can see four possible scenarios.

Do Nothing + eB2B Implodes

Hope is not a strategy. No brand likes to gamble when its moat is under attack. Do Nothing - is an unlikely scenario. Take the case of Patanjali - when the brand made a splash in the CPG market, all the leaders spent no time building a "naturals" portfolio. Although "Do Nothing" could have worked as Patanjali fizzled out in most categories, covering off the threat was essential.

Do Nothing + eB2B Grows

Unlikely scenario again, but only incumbent hubris can lead to this. The end result? Brands will slowly recede distribution to eB2B.

Most distributors in a brand's direct distribution network are family businesses. This pool is now ageing, their performance is not what it used to be a couple of decades back. Moreover, most distributors don't have a proper succession plan. The next generation of distributors is keener on other business opportunities with higher ROI. Today's market has many possibilities, unlike in the 80s or 90s when the family entered distribution.

The new distributors will churn faster. In a market muddled with so many players, pricing issues, and competitive last-mile service levels, it's hard for a new distributor to establish a strong business. At some point, the churn levels will surpass the appointment rate, and gradually brands will cede markets to eB2B operators.

If brands are ceding control, they prefer competition in the space - the more eB2B players, the better. Brands are today working with logistics providers who want to get into distribution. Strategic partnerships and investments in partners cannot be ruled out.

Why would brands prefer competition? Because it will affect the product portfolio and innovation. No CPG portfolio is made up of winners alone, there will be laggards and losers, and brands carry them. eB2B operators will only pick the creamy layers of brands, so what happens to the laggards? In the direct distribution, brands pushed laggards with incentives and offers, and they would want to retain this flexibility.

Side Note: For all the app-based claims, most eB2B last-mile is powered by a walk-in salesperson. A salesperson can't push more than a handful of brands during each kirana visit. For this reason, eB2B players pick only the creamy products that sell themselves. Even if the kirana store buys using the eB2B app, they will not scroll beyond two pages and will mostly pick the products with the best offers.

Re-think Distribution + eB2B Implodes

If brands read the expires by date on the current direct distribution model, they will move quickly to cover the risks. It's an excellent opportunity to replace the existing model with a leaner model - fewer, large distributors with technology to provide e-commerce-like service to retailers. We can draw lessons from Amazon's handling of Cloudtail.

When Amazon has decided to replace Cloudtail with fewer, smaller distributors (relatively speaking, of course). Amazon is partnering with entities that can invest at least a few hundred crores. Amazon will not co-own any distributor but will work closely with the appointed entities on technology, inventory etc. If Amazon can assure its partners of a good throughput, distributors will see a fast stock turnover and cash.

Another case to look closely at is Asian Paints. The paints leader started decades back on this journey. Asian Paints invested in technology and data to build a daily prediction engine that estimates demand at each dealership. The company replenishes stock at its dealership 2-3 times daily using this prediction data. Asian Paints also made investments in logistics to ensure that their last-mile service levels are maintained. A few decades back, such moves of direct distribution and high inventory risk would have been laughed at. Not anymore. The large CPG brands may not supply direct to kirana, but they can have a leaner model.

What's stopping the brands? Maybe it's the margin pressure in the short term. But protecting margins now might mean losing it a few years later.

Even if the current eB2B operators implode, more experiments are happening to disrupt the kirana distribution model. So, brands should move and reimagine the distribution while they still can.

Re-think Distribution + eB2B Grows

With a reimagined (discussed in the previous scenario) competitive distribution model, the brands will be better able to handle the pressure from eB2B. Of course, channel conflicts will not go away, but the chaos will be manageable.

The brands with a diverse category portfolio might be able to re-wire their distribution faster. We can't say the same about single or two category brands.

Watching HUL

Many credit HUL for pioneering the direct distribution model in India. We can't say for sure, but HUL does experiment a lot - not only with the products but also with the distribution. So it will be good to learn more about what HUL is thinking. We can dig through its annual reports and investor presentations for some information. The following illustration from two years back summarises their experiments well.

Shikhar, HUL's retailer ordering app, is labelled eB2B in the illustration. It started as a vanilla ordering app, but HUL is also trying to sell competitor products through Shikhar. We can see an arrow go from HUL directly to the retailer and bypasses the distributor.

To support Shikhar, HUL also has a program called Samadhan (not in the illustration). Samadhan is a logistics program that will ensure next-day delivery to retailers.

Inventory and logistics are locked in, so what's left? Lending? Yes, HUL works with SBI to handle channel and retailer financing. Right now, it may seem like an external piece. As banking APIs improve, HUL will not hesitate to integrate lending into the Shikhar app.

Everything put together, we have an integrated eB2B arm for HUL. Of course, all this might be experimental, but the intent seems clear.

HUL's The U Shop started a coupons and deals platform. Now it is an entire e-commerce site. The shopping experience on The U Shop web is poor, but full marks for the experiment. Even P&G and ITC, both have extensive category portfolios, have set up their own e-commerce storefronts.

The most intriguing initiative from HUL is the Humara Shop app (earlier myKirana). The Humara Shop app allows kirana stores to create online stores, similar to the Dukaan app. Why does HUL need such an app when VCs have pumped millions into similar ventures? We just want to help the retailer go digital can be a simple explanation. The alternative hypothesis could be that HUL wants to understand if this approach can be a viable entry point to build a direct relationship with a kirana store.

Well, HUL is experimenting and preparing. We should not be surprised if Shikhar eventually becomes a complete eB2B player. No one can stop HUL from buying competitor products from wholesale markets and selling to a kirana on Shikhar.

… in conclusion

It's time for brands to review their direct distribution efforts. Of course, brands would like to maintain the status quo, but the rise of more organized channels will force their hand. The eB2B operators are not going anywhere. In fact, more organized players will enter the space.

The brands must choose between short term sacrifice of margins, increased capex and long term loss of distribution control. It’s not an easy choice for listed brands.

What do you think about this article? Love to hear from you.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and suggestions. You can write to insurgentbrandnews@gmail.com

This article nails the critical shift happening in CPG distribution. The traditional direct distribution model, long a fortress for legacy brands, is clearly under threat from integrated eB2B players who leverage technology, credit, and logistics to build stronger retailer relationships.

The point about kirana stores shifting loyalty from distributors to eB2B platforms due to better pricing, convenience, and financing options is especially on point. It highlights how digitization is fundamentally changing even the most entrenched traditional channels—impacting everyday staples, including popular Indian food products that form the backbone of kirana store inventories.

HUL’s experiments, like Shikhar and Humara Shop, show how legacy players are proactively adapting by building their own integrated models—blurring lines between brand, distributor, and retailer.

The four scenarios laid out offer a useful strategic lens for brands: Do nothing isn’t viable, and rethinking distribution while embracing eB2B’s integrated model seems the way forward.

Ultimately, brands that can balance tech-driven efficiency with strong local retailer relationships, especially in categories like Indian food products brands like https://thedesifood.com/ that rely on trusted community networks, will survive and thrive in this new ecosystem.

Great read — would love to see more deep dives into how regional distributors and kirana owners are responding on the ground.